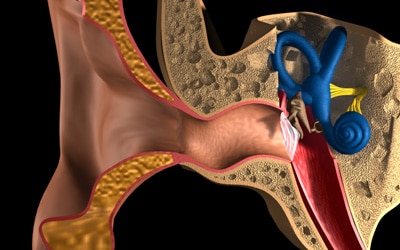

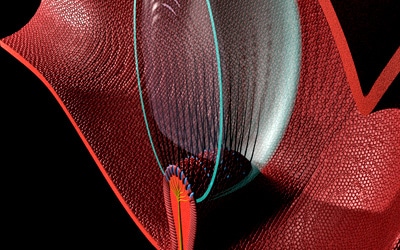

The auditory stimulus (sound, noise) is first received and relayed mechanically (as vibration) by the eardrum and the chain of auditory ossicles in the middle ear. In the cochlea this stimulus is then compressed by a highly complex fluid system and transformed into an electrophysiological nerval puls that can be passed on into the central nervous system. This transformation process takes place in every single auditory cell of the cochlea and can be described very well with our current knowledge of biology. It involves the movements of cilia (mobile hair-like appendages of the cellular membrane) and other working processes within the cell of the inner ear which use molecular cellular energy (ATP) – for example the ion-pumps of the cell membrane.

FUNCTIONING AND DISEASE

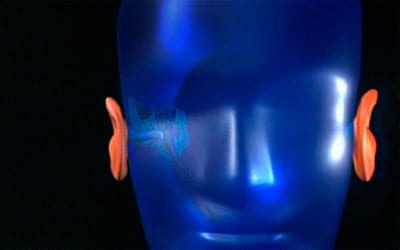

The ear

Organ of balance, hearing organ

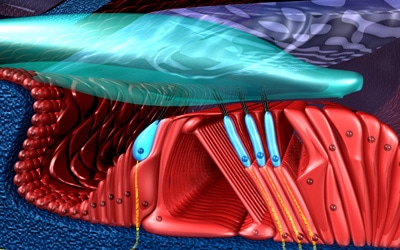

Auditory cell

Acute or chronic overtaxing of the cochlea inevitably leads to overstrain of the sensory cells (auditory cells) that work in it. Within the auditory cells an overtaxing and damaging of the respective cell organs takes place which in turn results in a decrease of their vitality. The cell, thus, suffers of a lack of ATP.

The mitochondria (the cell’s “power plants”) are responsible for the production of ATP (molecular cell fuel) within the cell.If, due to continuous overstrain, too little cellular energy (ATP) is available to the cells of the cochlea, either a gradual, subtle or a sudden damaging process of the entire auditory organ is triggered. We experience this as a sensation of pressure in our ear, as acute idiopathic hearing loss, as an acute or gradual onset of tinnitus, distortion of hearing, partial deafness etc.

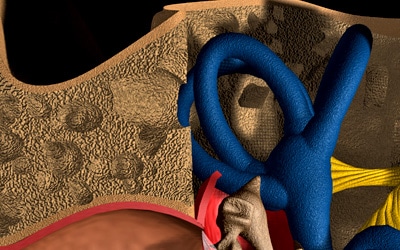

Organ of balance

Jelly crest

Cilia

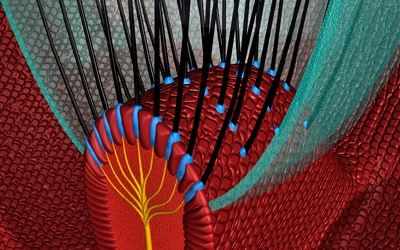

In the semicircular canals of our vestibular system (organ of balance) the respective position of our head and body is also transmitted by a fluid system to the sensory cells within this very organ. As in the cochlea this is achieved by way of so-called cilia movements. Within the cell itself almost the exact same ATP-consuming processes which take place during the hearing process in the cochlea are carried out: the mechanically received stimulus (cilia movements in the jelly crest) is transformed into an electrophysiological nerval pulse that can be passed on into the central nervous system.

As in the case of the auditory cells, the lack of cellular energy also actuates a damaging process within the affected organ. If, due to continuous overstrain, too little cell energy (ATP) is available to the cells of the cochlea, either a gradual, subtle or a sudden damaging process of the entire vestibular organ is triggered. We experience this as a sensation of pressure in our ear, acute rotatory and/or systemic/central vertigo, a gradual onset of vertigo, repeated episodes of vertigo etc.

Not only do the transmission processes within the labyrinth and the cochlea function very similarly, but they are also connected by a common fluid system. Hearing problems, therefore, often involve both organ systems at the same time and, thus, present with quite varied and individual symptoms. Of course, individually varying degrees of severity of the disorders affecting the inner ear – as in any other part/organ of the body – can be found. Naturally, this means that there are individually different courses of a healing.